Many civil society groups working with what could be termed “food issues” in the UK are, rightly, concerned about the impact of Brexit on British food and farming. These concerns range from financial support for farmers to the impact of new trade deals on food standards.

These and other food quality issues and standards are the focus of a great deal of campaigning and public outreach. But the introduction and regulation of genome edited/GMOs crops and foods seems to be absent from the webpages, social media and policy briefings of most food and farming NGOs.

Genetic engineering (now called genome editing) in agriculture and food is also a “food issue”. It has impacts on what we grow and eat, how we farm, how we regulate, what we trade and what choices consumers have. It has a more wide-ranging and potentially greater transformative potential than earlier manifestations of genetic engineering, yet it is receiving far less attention from civil society.

For example, during the early 2000s, the Sustain Alliance, which today represents 105 national public interest organisations working in food and farming, directly supported the Five Year Freeze campaign on genetic engineering and patenting in food and farming, following a member consultation. This support reflected a broad consensus position across the food, farming and environmental NGO and civil society sector.

With this survey we wanted to explore the extent to which this consensus survives and how robust it is today.

In the context of the government’s overarching policy of co-existence in farming and food technologies (e.g. that organic/agroecological farming, conventional and GM approaches can co-exist and find their own market and producer niches), we were also keen to discover more about what groups campaigning on “food issues” in the UK know about genome editing and what policies they have in place around it, especially regarding regulation and citizen involvement.

The survey was circulated to all members of the food and farming NGO umbrella group Sustain – the Alliance for Better Food and Farming, during May/June 2020. Sustain, has its own employees working on a number of discrete projects, as well as representing many national public interest organisations working at a local, national, regional and international level. Its members are diverse, ranging from trade unions to social marketing companies to food and farming campaigns and health education charities.

We also sent the survey out more widely to a further 28 NGOs working in food and farming who were not members of the Sustain Alliance.

Out of a potential pool of 133 a total of 37 organisations responded by filling in the survey.

These organisations included single issue groups, umbrella organisations/alliances, animal welfare groups, healthy eating groups, farming and land management groups as well as those representing organic/biodynamic/regenerative agriculture, community supported agriculture and smallholders.

Comment

Today the introduction, and push by governments and the research establishment, of new genome editing technologies – along with emerging threats to food, farming and environment caused by climate change – has created new conditions in which civil society organisations have to operate.

We wanted to explore how, and if, the past ‘coalition of caution’ has survived and whether that narrative is still informing campaigning around food and farming today. We were also keen to understand whether organisations had begun to address the notion of technological and market co-existence between different approaches to farming and food production.

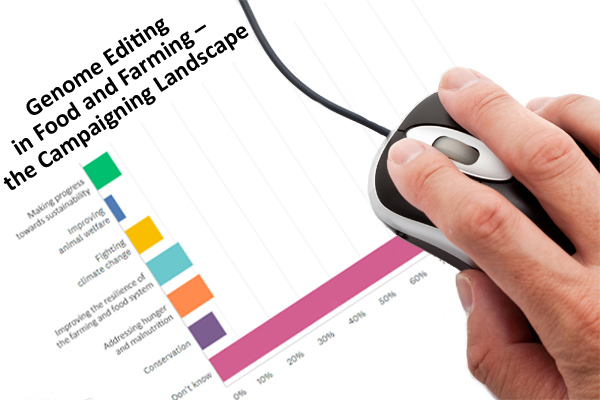

The results indicate that amongst the UK’s food and farming organisations, a new dynamic is at play which is less cohesive, less engaged, more cautious or hesitant than was expressed by many of these same groups in the early days of genetic engineering in agriculture.

- Nearly half of the responding organisations have no official position on genome editing technologies.

- The largest number of respondents favour a moratorium rather than an outright ban. A significant number expressed uncertainty but some think it should be allowed and has potential role in tackling global challenges.

- There is support for government-based regulation, labelling and ongoing monitoring, but some uncertainly about the role of citizens.

From the answers and comments we received, we tend to the view that there is a fairly low level of detailed knowledge on the issue of genome editing. For example, although just over half (21 organisations) claimed awareness of different methods of genome editing, none mentioned any specific method or scientific research to suggest they were following the issue closely.

Similarly, there were few comments expressed about how the implementation of genome editing technology as a policy can interact or co-exist with non-GMO approaches.

The language used in the comments often reflected familiar soundbites and suggested that views were predicated on wider values-based concerns or concern about corporate control of agriculture and lack of trust in government, rather than technical or scientific assessment.

This is important. If NGOs and civil society are going to demand regulation and greater democratic control over genome editing or any future ‘high tech’ technology, then there needs to be clarity on what that regulation looks like, how citizens will be engaged and how genuine transparency can be assured. The same points apply to the demand for a moratorium – how will it look, be structured, decided and – importantly – concluded?

At the moment the indications are that UK NGOs and civil society are, in general, unprepared to make a meaningful contribution to policy and regulatory development in these areas. There appears to be a very low level of engagement with deeper issues, either internally or as part of their outreach to policymakers or the public. This work is left largely to specialist organisations that work daily on the issue of genome editing.

This is a real concern given that the genome editing ‘genie is out of the bottle’ and a large majority of organisations said that they believe genome editing is relevant to their work now or will be in the future.

To strike a note of optimism, however, it is promising that we had a reasonable number of respondents and that many of the accompanying comments were thoughtful and nuanced.

There is a need to build a viable and effective new ‘coalition of caution’ over genome editing technologies in agriculture and food – one that does not separate genome editing specialist organisations from the mainstream of food and farming ‘issues’. Given focus and resources, and a greater willingness to draw from the pools of expertise which exist, there are indications that this can be done.

- The report including full comments can be downloaded here.

- Results of some of our other recent surveys can be found on our Viewpoints page.