A group of 18 scientists and bioethicists from seven countries has called for a “global moratorium” on all clinical uses of human germline editing — that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to ‘re-engineer’ humans.

The commentary, which appeared in the journal Nature, was led by Professor Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, the signatories included CRISPR pioneer Professor Emmanuelle Charpentier at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin, and leading CRISPR researcher Dr Feng Zhang, also at the Broad Institute.

While its recommendations have frustrated some stem cell scientists, it has been broadly welcomed and was given strong backing by Francis S. Collins, the director of the US National Institutes of Health.

The call was unique in acknowledging that editing the human genome is not simply a science and technology issue. It noted that many religious groups find “the idea of redesigning the fundamental biology of humans morally troubling”. It also acknowledged power hierarchies, noting that “Unequal access to the technology could increase inequality. Genetic enhancement could even divide humans into subspecies.”

A framework needed

The scientists stress they are not calling for a permanent ban but an international agreement not to greenlight germline editing leading to pregnancies before there is an agreed international framework in place.

The write “…we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations, while retaining the right to make their own decisions, voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met.”

Those conditions include giving public notice of its intention to engage in germline editing and consulting with other nations about “the wisdom of doing so”. The scientists also suggest taking two years to ascertain whether there is “broad societal consensus” about whether germline editing is appropriate.

In addition, they recommend a coordinating body to provide information and reports about germline, possibly under the auspices of the World Health Organization.

Gene-edited babies

The call for a moratorium was triggered by the international outcry and inevitable ethical questions surrounding a Chinese biophysicist, He Jiankui, who claims he created the first genetically modified babies late in 2018.

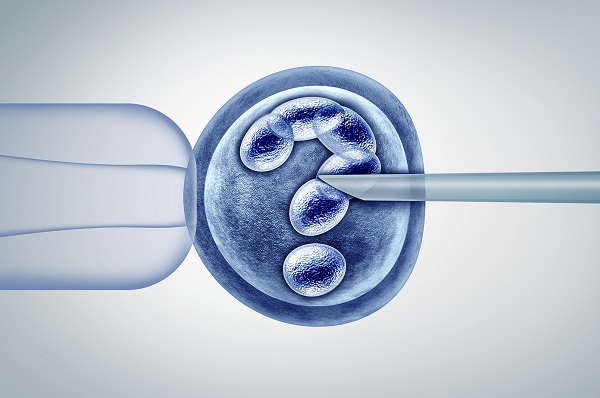

He Jiankui says his goal was to edit embryos to give them the ability to resist HIV infection by disabling the CCR5 gene, which allows HIV to enter a cell.

He used a CRISPR technology to edit human embryos to give them the ability to resist HIV infection by disabling the CCR5 gene, which allows HIV to enter a cell.

CRISPR has only recently begun to be used to treat diseases in adults, and only limited experiments have been performed on animals.

No scientific consensus on safety

The scientists calling for the moratorium noted that there is broad scientific consensus that germline editing is not yet safe or effective enough to be considered for clinical use.

They also highlighted the distinction between “genetic correction” – editing a rare mutation that has a high probability of causing a severe single-gene disease – and “genetic enhancement”, the attempt to improve human individuals and the species.

They further note that even efforts at genetic correction, when undertaken in order to cure a disease, can have unintended consequences.

For example, a common variant of the gene SLC39A8 decreases a person’s risk of developing hypertension and Parkinson’s disease, but increases their risk of developing schizophrenia, Crohn’s disease, and obesity.

Its influence on many other diseases and its interactions with other genes and with the environment, they say, remains unknown.

Conflicting views

Not everyone agrees with the suggestion of a moratorium.

Dr Beth Thompson, head of UK and EU Policy at the Wellcome Trust, commented “We do not agree that a moratorium is necessarily the best way to navigate this issue. Finding the right governance approach is critical,’

One of the inventors of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, has said that she supports “strict regulation that precludes use” of germline editing until scientific, ethical, and societal issues are resolved. “I prefer this to a ‘moratorium’ which, to me, is of indefinite length and provides no pathway toward possible responsible use.”

The suggested moratorium, however is not indefinite. The scientists are calling for a fixed period – perhaps five years – when no clinical uses of germline editing are allowed worldwide.

“It will be much harder to predict the effects of completely new genetic instructions,” they write, “let alone how multiple modifications will interact when they co-occur in future generations. Attempting to reshape the species on the basis of our current state of knowledge would be hubris.”

A post-script

This issue does not directly affect the discussion of genetic engineering in food and farming – or does it? The complexities and uncertainties of re-engineering living creatures, whether they be human or other animals, are often glossed over in the enthusiasm to bring new technologies to the fore.

There is a concerted effort now to use CRISPR to genetically engineer farm animals for a variety of purposes including for food and for pharmaceuticals. This, too, raises numerous concerns around precision, unintended consequences, ethics, religious belief, welfare and safety.

Animals are regarded as sentient beings in EU law and although it is still uncertain whether this acknowledgement will be transferred to UK law post-Brexit, environment secretary Michael Gove has promised to make “any necessary changes” to UK law to recognise that animals can feel pain. What, then, should the new conversation around genome-edited animals look like?