Everybody is talking about ‘sustainability’ these days. But what does that actually mean?

A new report from A Bigger Conversation – Rethinking Sustainability – Life-centric Agriculture in a Techno-centric World – argues that the concept of sustainability has become distorted and compromised, and needs to be radically rethought. It explores how we can shift to a life-centric approach, linked to a core philosophy that sustainability must first and foremost sustain life.

Although the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” have been ever present in most, if not all, discourse about policy, politics, business and general human behaviour throughout the world since they emerged in the late 1960s and 70s, they remain unclear and contested, honoured but not respected.

Tracing the history

Fundamental differences exist – especially around the compatibility of economic growth, planetary boundaries and societal values – but these have largely been ignored. The dramatically sharpening of the threats which concerned the early sustainability thinkers, and the emergence of new technologies allied to corporate capital, global markets and regulatory change, mean these differences cannot be ignored.

The predominant approach to policies claiming to address sustainability ostensibly sought a balance between environment, society and economy – the ‘triple bottom line’ approach. In practice, this is market, business and economy centred and, as the Sustainable Development Goals reveal, other concerns have to fit around them. The failure to achieve these goals alongside the increasing failure of the world to live within planetary boundaries demonstrate how unsustainable and unfit for purpose a market/business/economy-centric approach to sustainability is.

Yet, policy makers, politicians, business interests, research establishment, the media are doubling down economic growth (relabelled ‘green growth’) and increasing productivity as the driver of sustainability but now with a ‘techno-centric’ approach based on new, disruptive technologies, sweeping away precautionary regulation, democratic oversight and giving precedence to a few global corporate interests. This technocapitalism is already integral to many areas of our economies and lives. It is likely to fundamentally transform how we live but there is no reason to suppose it will make how we live more equitable or more sustainable.

There is an urgent need to move away economic and techno-centric sustainability towards a life-centric approach more in line with the earlier wholistic concepts of sustainability of living within planetary boundaries, sufficiency, precaution and equality.

A radical rethink

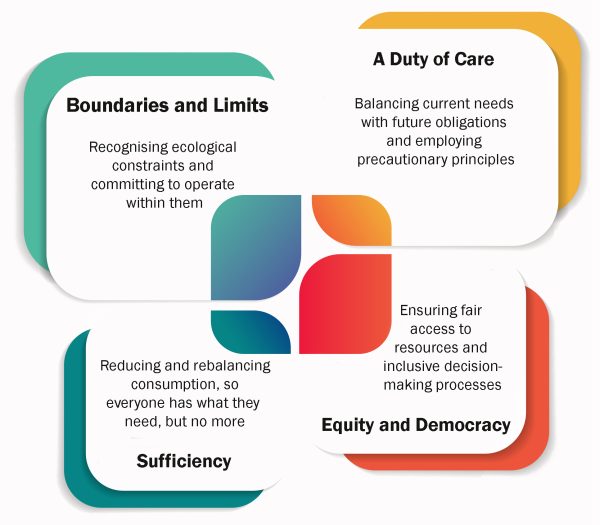

In our new report – Rethinking Sustainability – Life-centric Agriculture in a Techno-centric World – we propose a ‘life-centric’ approach to built on four key pillars: Boundaries and limits, A duty of care, Sufficiency and Equity and democracy.

Further, we advocate implementation criteria of clarity and transparency on trade-offs, timelines, decision-making on whether and how sustainability measures and policies are transitional, incremental or “finite state”. This includes ensuring that finite-state sustainability is not compromised during transition.

As it is fundamental to life and wellbeing, we have based much of our considerations of sustainability from the perspective of agriculture and the food system.

Whilst there have been benefits, the industrialisation and intensification of agriculture has led to significant environmental problems, including pollution, loss of biodiversity, and ecosystem degradation. These are well-documented, as are the positive and adverse changes in food and the food system that accompanied agricultural intensification.

The Green Revolution sought to use technology and inputs to increase productivity and sustainability – primarily through an income and trade generating market focus. This evolved into the twin approaches of Sustainable Development and Sustainable Intensification both technology and market driven, exemplifying the triple bottom line approach and its failure to deliver sustainability – or in agricultural terms, healthy food, environmental and nature protection.

Sustainable intensification has provided the context – or excuse – for the development of genetic engineering technologies with their accompanying narrative of using modern technology to reduce environmentally damaging inputs whilst increasing productivity. The recently emerged iterations – ‘net zero’, ‘nature based solutions’ and ‘climate smart agriculture’ – use the same narrative. They also have the same characteristics; a reductionist mindset reducing the scope of sustainability to a technology and market focus – in this case with a new twist of data and digitally based carbon and biodiversity credits – and a systemic avoidance of social issues.

Gene editing: a case study

As a case study exercise we examined gene editing – the fastest growing genetic engineering application in agriculture – against our life-centric perspective and framework for sustainability and found it to be incompatible.

From development to application, it is part and parcel of technocapitalism, heavily grounded in corporate power that seeks to commodify all aspects of our lives, to disrupt and control the intrinsic interconnectedness of all living things. The structures, drivers, finance and owners of genetic technologies have no recognisable duty of care to anything outside of their own growth dynamic based on monetised data and intellectual property rights (IPR) that generate profits but also create and maintain a web of technological lock-ins.

However, our framework doesn’t categorically rule out a role for some applications of gene editing as part of a transition or incremental pathway to sustainability. Our proposed implementation criteria provide a structured approach for evaluating each application on its own merits, while keeping an eye on uncertainties and ethical considerations and a focus on long-term sustainability.

We considered the sustainability claims of applications of gene editing along these lines and found that the lack of transparency and independent evidence a significant obstacle. Whist there was a good deal of projection there were notably few actual applications little proof that any them are or even could make a significant contribution to a transition to life-centric sustainability.

Moving forward

We recognise that the practical implementation and development of these pillars is challenging. There is much work to be done and this ‘outside the box’ thinking can easily be dismissed as fanciful.

There would be inevitable resistance from established agricultural industries, from economic pressures and global market forces. There would be initial lack of consensus on specific metrics and standards, as well as discussion about balancing short term productivity with long term sustainability. Crucially, consensus would require a commitment to a multi-faceted approach, combining policy measures, economic incentives, education and community engagement.

But as Rachel Carson wrote in 1962: “We in this generation, must come to terms with nature, and I think we’re challenged as mankind has never been challenged before to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves.”

On many levels, things are much more complex now than then and we have to find new ways to meet that challenge.

- Download the full report Rethinking Sustainability – Life-centric Agriculture in a Techno-centric World

- Download the Executive Summary of Rethinking Sustainability – Life-centric Agriculture in a Techno-centric World