While promising, techno solutions in agriculture including more widespread use of a variety of genetic technologies in the lab and in the field, also bring inevitable questions. A new report asks and whether such innovations free us from, or perpetuate, “agribusiness-as-usual”.

Growing trends towards artificial intelligence and geoengineering in the food sector put forward by big corporations will only perpetuate “agribusiness as usual”, according to a new report.

Proteins produced in petri dishes, AI-managed farms, and food-delivery drones will help solve the hunger problem whilst at the same time reducing the impact of food production on the environment. This is the belief that many are betting on and it’s leading to a growing trend of corporations like Amazon, Alibaba, Facebook and Microsoft teaming up with agribusinesses that already dominate the food industry, according to a joint report by Belgium-based IPES Food and the US-based ETC Group.

“There’s clearly a huge interest in applying all of the new technologies, of what’s being called the Fourth Industrial Revolution, to food systems and disrupting them,” said Nick Jacobs, director of IPES Food and co-author of the report.

However, while promising, the authors claim that these new technologies will only accelerate environmental breakdown and food insecurity unless civil society can work together across regions and sectors so that innovation also benefits small scale farmers, consumers and other food actors.

Why this matters

The pandemic has underscored the food problem that has already been simmering for years. Over 690 million people around the globe went hungry in 2019 and at least three billion could not afford a healthy diet, according to UN figures. According to estimates by the World Food Programme, the Covid crisis could have pushed another 270 million people over the brink of food insecurity in 2020.

At the same time, the food supply chain is responsible for roughly a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions and has accelerated biodiversity loss and land degradation.

Revolutionising food

Closing the hunger gap while reducing the environmental impact has thus become a global goal, with many believing that technological innovation is the key to unleash the transformation needed.

This has paved the way for digitalisation and automation throughout the whole food chain, from a tomato growing on a farm to the caprese salad on our plates.

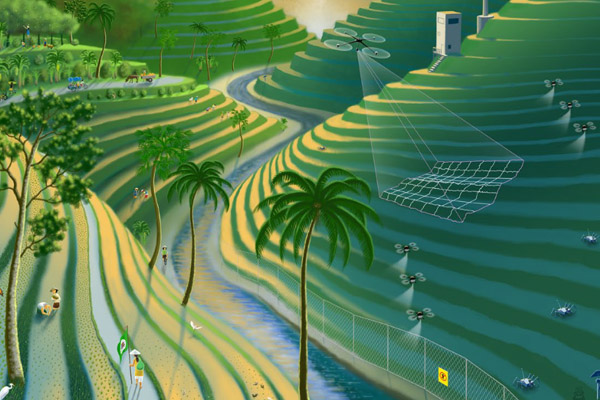

As part of the new “precision farming” techniques being developed, drones are being used to spray crops with pesticides to target specific areas, thus reducing the amount of products used and optimising costs for farmers.

Apps are being developed to improve transparency and allow for better tracking of products across the supply chain.

Emerging e-retail and food delivery markets, which have accelerated thanks to the pandemic, are an opportunity for brands to better understand and meet buyers’ demands through algorithms.

The report also points to two areas, which are less developed but that are expected to increasingly play a role in the future of food: molecular technologies – most commonly associated with GMO plants – and nature modification – manipulating earth system processes like the weather or the carbon cycle.

Giants moving in

With enormous economical potential, powerful companies like Amazon, Alibaba and Facebook are increasingly moving into these new fields posing a risk of new monopolies and cartels being formed, although this time with food.

According to the report, within the next five years the agricultural sector will be second in drone use after the military. Amazon and Microsoft are teaming up with farm equipment giants to provide the cloud computing infrastructure needed to host the data for precision farming, the report says.

“The way food systems are headed, with the concentration of power in the hands of these companies, and the coming together of agribusinesses with cloud computing companies, private equity firms and data companies, it is putting food security at the mercy of very centralised systems,” Jacobs explained.

Such concentration would perpetuate many of the social and environmental challenges that the food sector faces today, and even accelerate some of them, including land, ocean and resource grab, according to the report.

“This could accelerate some of the trends we’re seeing already, notably farmers moving off the land for exodus and creating huge risks with regard to resilience,” he added.

The case for open access

Despite depicting a scenario that sends shivers down the spine, the authors also highlight how technology can be used for the good of smaller food actors.

“There are huge benefits to be gained from information and technology, allowing people to access the decision making processes that affect our food systems, such as a UN negotiation or a town hall meeting,” Jacobs explained.

“We see technologies as being part of production systems, and also helping to build more inclusive governance systems. The difference here is that the technology that we need would be based on open access and owned by cooperatives or by people rather than the current situation, where people are surrendering their data and being nudged, with no control over it.”

To avoid the downward spiral, the authors suggest a series of strategies for civil society to spark a movement over the next 25 years that could lead to sustainable food systems. If successful, the report estimates that around $4 trillion could be shifted from the industrial food chain to food sovereignty and agroecology, including $720bn in subsidies currently going to big commodity production, and as much as $1.6 trillion in healthcare savings from a crackdown on junk food. These actions could slash food system emissions by 75 per cent, the report states.

Among the steps that could be taken to ensure that technological innovation serves that purpose is shifting public and private investment towards supporting open access solutions, Jacobs explained.

Another aspect, he added, is regulating corporations: “One of the key strategies we lay out for civil society is to push for antitrust treaties to avoid excessive concentration of corporate power which enables technological solutions to be put forward without any benefits.”

Asked if he believed big corporations could be convinced to steer food systems in that direction, Jacobs said that “some companies seem to be fundamentally monopolistic in the way they work so it would be naive to imagine that we could work with all of the biggest companies to develop the solutions.”

“If we look at the struggles over vaccines right now, it’s very illustrative. There are deep divisions between a sort of philanthro-capitalist approach and others calling for fundamental rethinking of intellectual property rights, of the way we share information and of people’s right to develop medicines and vaccines.”

- The report, A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045, is available in English, French and Spanish and can be downloaded here.

- This article originally appeared at Geneva Solutions, licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0.