As we await the report on the UK government’s public consultation on ‘The Regulation of Genetic Technologies’ it is a germane moment to address the hitherto under-explored distinction between traditional and technological food, feed and seed.

The consultation sought views on what the UK Department for the Environment and Rural Affairs (Defra) said were gene edited organisms “possessing genetic changes which could have been introduced by traditional breeding”. Indeed, in an effort to associate genetic engineering technologies with ‘traditional’ ones, traditional plant breeding technique is mentioned 18 times in Defra’s consultation document. The document also alludes to genome-edited organisms that “could have been produced naturally”.

The notion that genetic technologies are merely an extension of ‘traditional’ agricultural breeding forms the core reasoning with which Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government intends to waive through non-traditional, novel plant breeding techniques and justify the free circulation – without risk assessment, with little to no socio-economic impact assessment and without labelling – of gene-edited food in England and indeed the rest of the UK.

The logic of this approach appears to be that if a technology can be classified, interpreted, labelled and defined as either ‘traditional’ or ‘natural’ then expensive and overly protective risk assessment can be ditched, consumer confidence will grow and gene-edited technologies can be free to circulate widely into the UK consumer market.

Traditional produce, food and feed has been tried and tested for generations, hence its association with safety. As a result, food, feed and seed labelled ‘traditional’ and ‘natural’ elicits a high level of consumer trust. For this reason, the discussion around traditional plant breeding is crucial to understanding how the UK intends to reform agricultural genetic technologies encompassing both plants and animals.

Novel, anthropogenic and industrialised

A useful way to compare and contrast traditional methods with modern methods is to consider whether any seed, food, feed or process is, or has been, linked to an intellectual property rights. Plant (and animal) intellectual property rights act as useful markers with which to determine what can justifiably be described as traditional, natural and what cannot.

Plant breeders can benefit from two intellectual rights – a plant variety right (PVR) or a patent. These rights, however, are conditional on three basic conditions:

- First, the inventor of a technology involving living organisms must prove that their creation is new and/or novel. If the living organism exists or is part of traditional knowledge the application fails.

- Second, the technology involving living organisms must be anthropogenic. It must not be natural. If it exists in nature it fails the first test of novelty. If it exists in nature it cannot be described as innovative, and the application fails.

- Third, it must be capable of commercialisation and or industrialisation. If the innovation is created out of sheer intellectual curiosity and/or is limited to academic research purposes the application fails.

Let us consider each intellectual right in turn.

Plant variety rights

The modern plant breeding industry makes money from its new varieties via payments achieved through plant variety rights (PVR). To qualify for a PVR, modern agricultural breeders are required to make their novel varieties New, Distinctive, Uniform and Stable (NDUS). If the variety seeking property rights already exists or were it commonly found in nature it would not fulfil the PVR criteria and an application for the right would almost certainly fail.

This form of intellectual right began in the 1960’s but has been developed considerably over the decades to incentivise more and more anthropogenic plant breeding. As a result, most modern plant breeders are employed by universities or corporations. Very few are farmers, market farmers or hobby gardeners.

The PVR right encourages plant breeders to create new varieties to certain specifications. Wheat or barley can be bred to grow to a uniform 50 cm. Maize can be bred to contain extra fructose. Rapeseed oil can be bred to contain less acids. All are new, distinctive, uniform and stable.

The development of PVR has altered the nature of British farming and the rural landscape. It has encouraged agricultural produce that is a lot less varied and a lot more uniform, standardised and industrialised.

Describing any new or novel agricultural variety which is the beneficiary of a PVRs as ‘traditional’ or ‘natural’ is problematic. Two public authorities – the UK Plant Variety Office and Defra – would be offering two contradictory legal definitions. The first would describe a PVR as new, uniform and standardised whilst the second, Defra would be describing this form of breeding as traditional.

For the purposes of the Defra consultation, the logical conclusion is that plant technologies benefitting from a PVR should not be described as traditional.

Patents on living agricultural technologies

Patents are, by far, the most valuable and commercially interesting intellectual right for plant or agricultural breeders.

PVRs offers breeders weaker rights and are harder to enforce, particularly in developing countries. Patents, on the other hand, offer inventors of living agricultural technologies what is referred to as an ‘absolute monopoly’ valid for 20 years. They are strictly enforced across most developed economies’ jurisdictions and public authorities typically come down hard on patent infringers – including those in developing countries.

In return for such a valuable right, public authorities have developed even stricter criteria than PVRs to prevent unsuitable patent protection. To be awarded a patent, the creator of technological plant and animal varieties must go to great lengths to prove they are the true and first inventors of such creations. They must prove that the technology is inventive and manmade. Crucially, the technology cannot be natural.

CRISPR pioneers battle to prove novelty

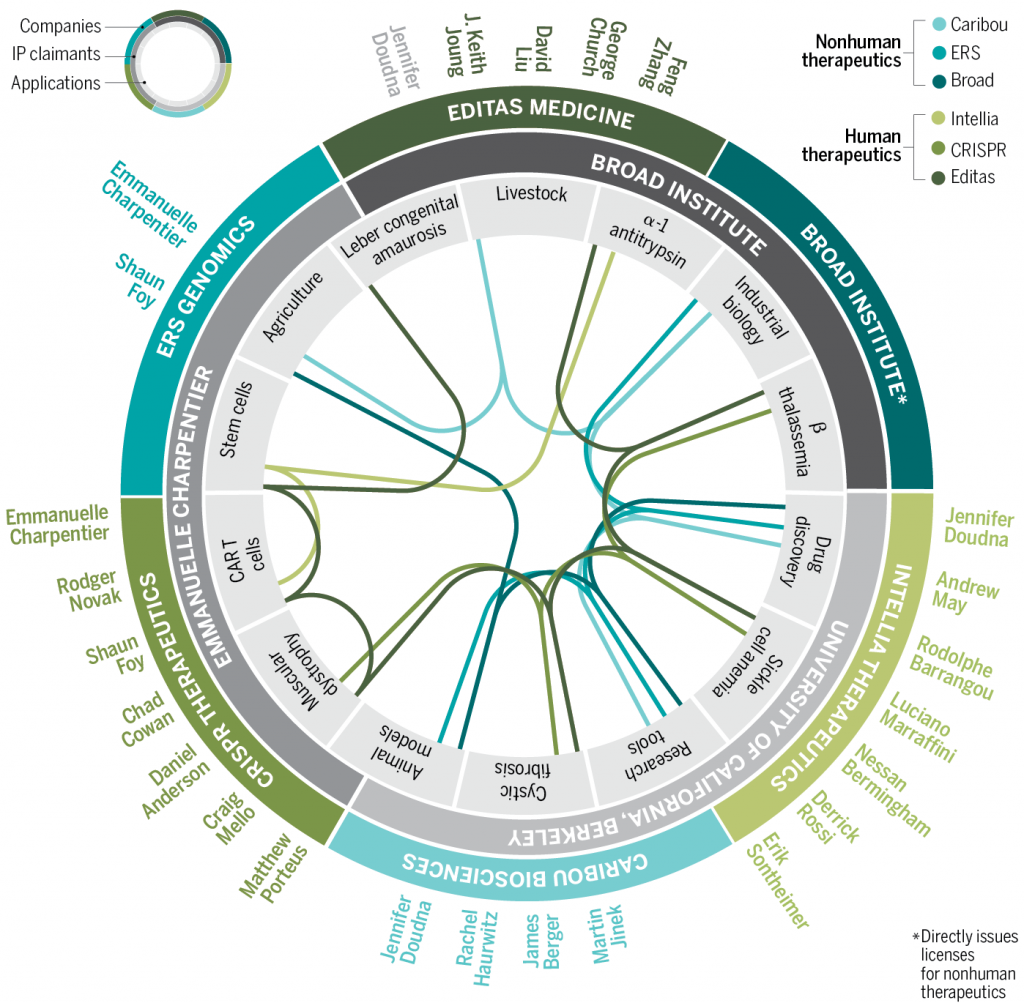

CRISPR Cas-9 technology was pioneered by academics working out of university research departments – not by farmers, market farmers or hobby gardeners. George Church, Jennifer Doudna, Feng Zhang and Emanuelle Charpentier are senior Professors working at prestigious university research institutes. They are fairly representative of the modern, technologically-driven plant breeder.

The four CRISPR pioneers were once collaborators and colleagues but are now involved in a bitter patent dispute over who owns the right to the core technology:

“The small community of researchers was rent apart by concerns about intellectual property, academic credit, Nobel Prize dreams, geography, media coverage, egos, personal profit, and loyalty. Adding to the divisive forces were the interests of the prestigious and powerful institutions that had a stake in the spoils – which in addition to UC, Broad, and Harvard included the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge and the University of Vienna.”

All four CRISPR pioneers are said to have paid a staggering EUR 16 million in legal fees to prove that their gene editing technology is novel, inventive and industrial.

Alongside her many other accolades and achievements, Doudna heads the Innovative Genomics Institute and is responsible for 27 research projects on gene edited agriculture. Caribou Biosciences, co-founded by Doudna signed a deal in 2015 with Du Pont to serve gene-edited maize to the American consumer.

She is not alone. ERG Genomics is a company set up by Charpentier to licence, amongst others, agricultural bio-engineered agricultural and livestock products. Indeed, all four CRISPR pioneers have founded a number of independent companies with which to licence their novel technologies. Some for medical and pharmaceutical purposes – a lot for novel agricultural purposes.

The CRISPR pioneers however are by no means the only researchers working on novel gene editing patents.

A study published by Nature Biotechnology noted that as of 31 May 2017, 352 patents had been filed for CRISPR Cas-9 gene editing of plants and animals – and these did not include patents which have broadly been described as ‘technological improvements’ but which relate to gene editing agricultural species – predominantly pigs, cows, buffalo, goats, sheep, chicken, birds and fish and rice for plants but also other plant species. The authors of the report note:

“The reason for not grouping these agricultural technical improvements with the above-mentioned ‘technological improvement’ category is that agricultural biotechnologies may be more controversial than other biotechnologies, and this could translate in differential involvement of countries.”

Agricultural and horticultural gene editing technologies are clearly important to and intrinsically linked to the patent process.

So, is gene editing ‘traditional’?

Which brings us back to the core question that should be asked before the law on GMO food, feed and seed is reformed to give gene edited plants a free ‘pass’ into the marketplace: Are gene-editing methods traditional and would Defra be correct to allow gene editing technologies to be defined as such?

To reiterate: suggesting any new or novel patented agricultural technology is ‘traditional’ or ‘natural’ as Defra has done in the consultation on gene-editing technologies, is problematic. It clearly contradicts the legal position, which the UK Patent Office would have to take if it is doing its job properly, that a CRISPR Cas-9 agricultural patent means it is novel, inventive and industrial and therefore not, traditional and/or natural.

Consequently, the logical conclusion is that from a health and safety perspective as well as a sustainability perspective they cannot be described as safe and tested. Defra cannot assume gene-edited technology is benign and harmless and should not present it as such.

Acceptance of this brings other issues into the fore.

Precisely because modern, agricultural technologies in life sciences are, per IPR definition, entirely novel, uniform and anthropogenic a proper risk assessment is essential and should be an absolute requirement before such processes or products are authorised for use and given access to the English market.

From an economic point of view, regulators that claim to be working on behalf of rural interests should further be alerted to the monopolistic tendency of agricultural technology linked to intellectual rights. Far from creating a sustainable ‘green’ economy it may destroy traditional, sustainable, small scale English farmers as it has done in the US and elsewhere where anthropogenic breeding techniques linked to an intellectual right are extensively used.

The regulator acting on behalf of the public good must, in addition, be aware that the industrial and uniform requirements of agricultural intellectual rights (patents as well as plant variety rights) encourages the development of monocrops and agriculture. This in turn results in species loss, a decline in biodiversity and far fewer plant varieties than even our recent ancestors enjoyed. Once again, this is not sustainable.

Finally, English consumers and farmers have a right to know whether their purchases are novel, untested, artificial, synthetic and anthropogenic. As such, any foods derived from genetically engineered or gene editing processes, produce and/or ‘technological improvements’ that do pass strict risk assessments or essential use requirements should be labelled as such in order to protect this right.

Being given a legally sound basis to claim the right to tradition, heritage, naturalness and/or sustainability is a highly sought-after and commercially valuable right to claim.

If the UK government is prepared to gift this legal right to modern plant breeders engaged in gene editing and novel plant breeding techniques, it is crucial to consider whether the claim to tradition is justified or not before that right is gifted and cannot be returned.

- Kathleen Garnett is currently writing a Ph.D at Wageningen University on the governance of innovation in the EU. Her area of interest includes intellectual property rights, environmental law, the law of technology and innovation. In a self-employed capacity she advises a wide range of clients on strategic thinking, consultancy, and detailed analysis of EU law and policy. Sectors covered include regulation (technical standards in particular) but also food and feed; environmental law and policy.